Why Didn t Sumerians Continue to Live in Small Villages Like Their Ancestors

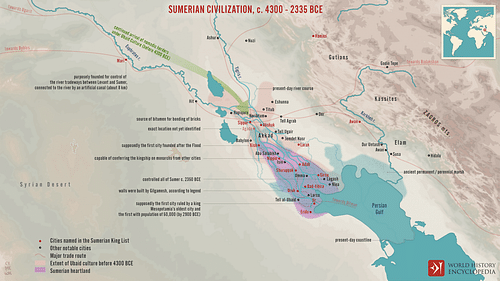

The Sumerians were the people of southern Mesopotamia whose civilization flourished between c. 4100-1750 BCE. Their name comes from the region which is frequently – and incorrectly – referred to as a "country". Sumer was never a cohesive political entity, however, but a region of city-states each with its own king.

Sumer was the southern counterpart to the northern region of Akkad whose people gave Sumer its name, meaning "land of the civilized kings". The Sumerians themselves referred to their region simply as "the land" or "the land of the black-headed people".

The Sumerians were responsible for many of the most important innovations, inventions, and concepts taken for granted in the present day. They essentially "invented" time by dividing day and night into 12-hour periods, hours into 60 minutes, and minutes into 60 seconds. Their other innovations and inventions include the first schools, the earliest version of the tale of the Great Flood and other biblical narratives, the oldest heroic epic, governmental bureaucracy, monumental architecture, and irrigation techniques.

After the rise of the Amorites in Mesopotamia, and the invasion of the Elamites, Sumer ceased to exist and was only known through references in the works of ancient writers, including the scribes who wrote the biblical Book of Genesis. Sumer remained unknown until the mid-19th century CE when excavations in Mesopotamia unearthed their civilization and brought their many contributions to light.

Follow us on Youtube!

Sumerian Votive Plaque

Development & 39 Firsts

Throughout the 19th century CE, European archaeologists descended on the Near East in search of ancient cities, tombs, and artifacts. None of these went to Mesopotamia to look for Sumerian cities because no one knew the civilization had ever existed – they were looking to excavate sites mentioned in the Bible such as Babylon and Nineveh and a mysterious place called Shinar – but they found much more than they were expecting.

No one knows where the Sumerians came from but, by c. 2900 BCE, they were firmly established in southern Mesopotamia. The history of this region is divided by modern scholars into six eras:

- The Ubaid Period – c. 5000-4100 BCE

- The Uruk Period – 4100-2900 BCE

- The Early Dynastic Period -2900-2334 BCE

- The Akkadian Period – 2334-2218 BCE

- The Gutian Period – c. 2218-2047 BCE

- The Ur III Period (also known as The Sumerian Renaissance) – 2047-1750 BCE

The origins of the people of the Ubaid Period are also unknown – as is their culture - but they left behind some intriguing artifacts and probably founded the first communities which grew into the later cities and developed into city-states during the Uruk Period. The Early Dynastic Period saw the rise of the kings, establishment of government and bureaucracy, and conflict between Sumerian city-states for land and water rights. The Sumerian cities were periodically united under a single king, as in the case of Enembaragesi of Kish who led Sumer against Elam in the first recorded war in history c. 2700 BCE. The Sumerians were victorious and sacked the cities of Elam.

Sumer was finally conquered by Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE) who made it the core of his multinational empire.

The later king Eannatum would reconquer parts of Elam c. 2500 BCE and Lugalzagesi would do the same c. 2330 BCE but these kings could never fully control the Sumerian city-states. Sumer was finally conquered by Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE) who made it the core of his multinational empire. He maintained control of the region by placing trusted officials in powerful positions in each city – including his daughter, Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), the High Priestess of the goddess Inanna at Ur (famous in her own right as the world's first author known by name). The Akkadian Empire held the region until the invasion of the Gutians who ruled until they were driven out by Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) and his son Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) who were responsible for the so-called Sumerian Renaissance which saw a rebirth of Sumerian culture following the Akkadian and Gutian conquests.

Sumerian Civilization, c. 4300 - 2335 BCE

Sumerian cities, before and after the conquests, grew rich from trade. The relative stability of the cities encouraged cultural growth, innovation, and invention. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, in his iconic work History Begins at Sumer, explores 39 "firsts" in the world which originated with the Sumerians:

- The First Schools

- The First Case of 'Apple Polishing'

- The First Case of Juvenile Delinquency

- The First 'War of Nerves'

- The First Bicameral Congress

- The First Historian

- The First Case of Tax Reduction

- The First 'Moses'

- The First Legal Precedent

- The First Pharmacopoeia

- The First 'Farmer's Almanac'

- The First Experiment in Shade-Tree Gardening

- Man's First Cosmogony and Cosmology

- The First Moral Ideals

- The First 'Job'

- The First Proverbs and Sayings

- The First Animal Fables

- The First Literary Debates

- The First Biblical Parallels

- The First 'Noah'

- The First Tale of Resurrection

- The First 'St. George'

- The First Case of Literary Borrowing

- Man's First Heroic Age

- The First Love Song

- The First Library Catalogue

- Man's First Golden Age

- The First 'Sick' Society

- The First Liturgic Laments

- The First Messiahs

- The First Long-Distance Champion

- The First Literary Imagery

- The First Sex Symbolism

- The First Mater Dolorosa

- The First Lullaby

- The First Literary Portrait

- The First Elegies

- Labor's First Victory

- The First Aquarium

The Sumerians also invented the concept of the city and one of the claimants to the title of "oldest city in the world" is the Sumerian Uruk. The earliest cities established in Sumer were:

- Eridu

- Uruk

- Ur

- Larsa

- Isin

- Adab

- Kullah

- Nippur

- Kish

The heart of the city was the temple complex, marked by the great ziggurats which would inspire the later tale of the Tower of Babel. Each city had its own protective deity who lived in the temple, protecting and guiding the citizens but, for the Sumerians, the city of Eridu – and its god Enki – held a special place.

The First City

Although modern-day archaeology has established that Uruk is the oldest city in Mesopotamia, the Sumerians themselves believed the first city in the world was Eridu, presided over by their god of wisdom and water, Enki, who raised it from the watery marshes and established the concept of kingship and order in the land. The establishment of Eridu by Enki was seen as a kind of golden age comparable to the biblical Garden of Eden as the home of the gods and birthplace of the rules governing civilization (known as the meh). Scholar Gwendolyn Leick notes:

The Mesopotamian Eden is not a garden but a city, formed from a piece of dry land surrounded by the waters. The first building is a temple…This is how Mesopotamian tradition presented the evolution and function of cities, and Eridu provides the mythical paradigm. Contrary to the biblical Eden, from which man was banished forever after the Fall, Eridu remained a real place, imbued with sacredness but always accessible. (2)

The 'fall' of Eridu had nothing to do with humanity's sins but with the cleverness of one of the most popular Mesopotamian goddesses, Inanna. In the poem Inanna and the God of Wisdom, the goddess travels from her city of Uruk to Eridu, home of her father Enki, and invites him to sit and have a few drinks with her and, as he drinks and becomes more and more jovial, he gladly hands over the meh to his daughter. Once she has gathered them all, she runs to her ship and brings them to Uruk, thus making her city preeminent and diminishing Eridu. Modern-day scholars believe this myth arose in response to the shift from an agrarian culture (symbolized by Eridu) to the urban development epitomized by Uruk, among the most powerful cities in the region.

Ur-Nammu

Government

Religion was fully integrated into people's lives and informed the government and the social structure. The Sumerians believed that the gods had formed order out of chaos and the individual's role in life was to labor as a co-worker with the gods to make sure chaos would not come again. The gods themselves, however, would reverse their own work later – returning the world to chaos - when humanity's noise and trouble became too great to bear.

The Sumerian work known as the Eridu Genesis (composed c. 2300 BCE) is the earliest version of the Great Flood tale.

The Sumerian work known as the Eridu Genesis (composed c. 2300 BCE and found in the ruins of Eridu) is the earliest version of the Great Flood tale later retold in the Atrahasis, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and the Book of Genesis. It relates how the gods destroyed humanity through a flood except for one man, Ziusudra, who is saved when Enki tells him to build an ark and rescue two of every kind of animal. Afterwards, the gods relent and determine to control the human population, and limit their annoying tendencies, by introducing death and disease into the world; thereby reestablishing order and setting a limit to human life and ambition.

The gods expected human beings to use their lives to help maintain order and this included finding a way to work together. The Sumerians took great pride in their individuality, as evidenced by the elevation of the patron deities of each city and intermittent rivalry and conflicts, but were required by the gods to set this aside in the interests of the common good. Kramer writes:

While the Sumerians set a high value on the individual and his achievement, there was one overriding factor which fostered a strong spirit of cooperation among individuals and communities alike: the complete dependence of Sumer on irrigation for its well-being – indeed, for its very existence. Irrigation is a complicated process requiring communal effort and organization. Canals had to be dug and kept in constant repair. The water had to be divided equitably among all concerned. To ensure this, a power stronger than the individual landowner or even the single community was mandatory: hence, the growth of governmental institutions and the rise of the Sumerian state. (Sumerians, 5)

The Sumerian King List, a document composed c. 2100 BCE in Lagash, lists all of the kings going back to the beginning of the world when the gods first established kingship in Eridu. The first king who is archaeologically attested was Etana, described as "he who stabilized all the lands" (Sumerians, 43) and the list then goes chronologically – often with impossibly long dates for the monarchs – down to the reign of the kings in c. 2100 BCE.

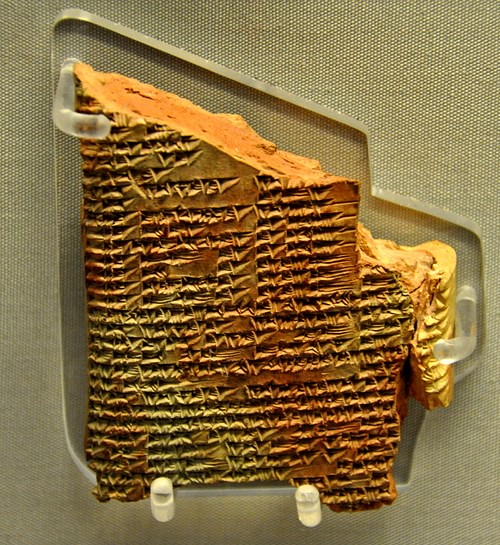

Legend of the Hero Etana Inscription

The Sumerian city-state was governed by a king, the Lugal (literally "big man") who oversaw the cultivation of the land, among many other responsibilities, and was bound to the gods to ensure their will was done on earth. The Lugal was initially head of a "household" – a closely-knit community, which pooled their resources – and the household concept would continue as the underlying power structure of the cities. With the rise of the cities and the development of agricultural innovations, the Sumerians changed the way human beings had lived, and would live, forever. The scholar Paul Kriwaczek comments:

This was a revolutionary moment in human history. The [Sumerians] were consciously aiming at nothing less than changing the world. They were the very first to adopt the principle that has driven progress and advancement throughout history, and still motivates most of us in the modern times: the conviction that it is humanity's right, its mission and its destiny, to transform and improve on nature and become her master. (20)

Contributions & Collapse

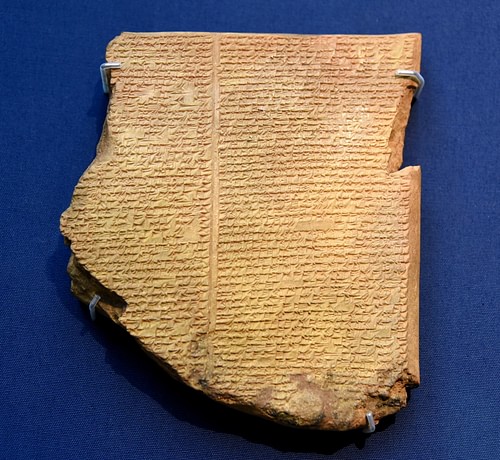

The cities of the Sumerians expanded, and when they needed more room and greater resources, they took them from others. During the Uruk Period, the culture developed rapidly, with perhaps the greatest invention culminating in the advent of writing c. 3600-3500 BCE. Early writing developed in response to the need for long-distance communication in trade and relayed basic information such as "two sheep – five goats – Kish" which was clear enough to the sender at the time but lacked the ability to inform a recipient whether the two sheep and five goats were coming or going from the city of Kish, whether they were alive or dead, and what their purpose was. This system would develop by the time of the Early Dynastic Period into the writing system which would produce such works as The Epic of Gilgamesh, Enheduanna's Hymns to Inanna, and many other great works of literature.

Flood Tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh

Sumerian became the language the lingua franca of Mesopotamia and established the writing system known as cuneiform which would later be used to record other languages. Gwendolyn Leick comments:

The more homogeneous cultural horizon of the alluvial plains [of Sumer] finds expression in the development of writing in a particular idiom. Why Sumerian came to be the language represented by writing is still uncertain. Mesopotamia was never linguistically or ethnically homogeneous and the personal names in the early texts clearly show that languages other than Sumerian were spoken at the time. (65)

Sumerian was well established as the written language by the late 4th century BCE and Sumerian culture, religion, architecture, and other significant aspects of civilization were as well. The literature of the Sumerians would influence later writers, notably the scribes who wrote the Bible, as their tales of The Myth of Adapa, The Eridu Genesis, and The Atrahasis would inform the later biblical accounts of the Garden of Eden, Fall of Man, and the Great Flood. Enheduanna's works would become the models for later liturgy, Mesopotamian animal fables would be popularized by Aesop, and The Epic of Gilgamesh would inspire works such as the Iliad and Odyssey.

The concept of the gods living in the city's temple, as well as the shape and size of the Sumerian ziggurat, is thought to have influenced the Egyptian development of the pyramid and their beliefs about their own gods. The Sumerian concept of time, as well as their writing system, was also adopted by other civilizations. The Sumerian cylinder seal – an individual's sign of personal identification – remained in use in Mesopotamia until c. 612 BCE and the fall of the Assyrian Empire. There was literally no area of civilization the Sumerians did not make some contribution to but, for all their strengths, their culture began to decline long before it fell.

The Ziggurat at Kish

The Sumerian civilization collapsed c. 1750 BCE with the invasion of the region by the Elamites. Shulgi of Ur had erected a great wall in 2083 BCE to protect his people from just such an invasion but, as it was not anchored at either end, it could easily be walked around – which is precisely what the invaders did. Even so, the culture had been struggling to retain its autonomy ever since the Amorites had gained power in Babylon. A shift in cultural influence, evidenced in many respects but, notably, in the male-female ratio of the Mesopotamian pantheon, came with the rise to power of the Semitic Amorites in Babylon and, especially, during the reign of Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE) who completely reversed the Sumerian theological model in elevating a supreme male god, Marduk, over all others. Temples dedicated to goddesses were replaced by those for gods and, even though the goddesses' temples were not destroyed, they were marginalized.

At this same time, women's rights – which were traditionally on par with men's – declined as did the great Sumerian cities. Overuse of the land and urban expansion, coupled with ongoing conflicts, are cited as the primary reasons for the fall of the cities. The correlation between the decline in the status of female deities and women's rights has never been adequately explained – it is unknown which came first – but it is a telling detail in the decline of a culture which had always held women in high regard. By the time the Elamites invaded c. 1750 BCE, the Sumerian culture was already deteriorating and the Elamites simply finished the process.

Discovery

The Sumerians are recognized today for numerous contributions to world culture, but this is a fairly recent development. Their history lay buried under sands for centuries and so any references to them in ancient works were misunderstood by scholars since there was no known referent for the allusions. The land of Shinar, in the biblical Book of Genesis, for example, was understood to allude to some region of Mesopotamia but the significance of that reference could not be understood as long as scholars had no idea any place like the land of Sumer – the biblical Shinar - had ever existed.

This situation changed dramatically in the mid-19th century CE when Western institutions and societies began sending expeditions to the Near East and the Middle East in search of physical evidence to corroborate biblical narratives. If a land such as Shinar had ever existed, it was reasoned, its ruins – along with those of any other structures and cities mentioned in the Bible – could be uncovered.

At this time, the Bible (specifically the narratives of the Old Testament) was considered the oldest book in the world and completely original. The story of the Garden of Eden, the Fall of Man, the Great Flood were thought to be original works written directly, or inspired by, the one true God of the Judeo-Christian tradition. The archaeologists and scholars who were sent on these expeditions were supposed to find hard evidence to support this claim but, instead, found exactly the opposite: they found Sumer.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Sumerians/

0 Response to "Why Didn t Sumerians Continue to Live in Small Villages Like Their Ancestors"

Post a Comment